New to Honeycomb? Get your free account today.

As discussed in the first article in this series, a Center of Production Excellence (CoPE) is a more or less formal, provisional subsystem within an organization. Its purpose is to act from within to change that organization so that it’s more capable of achieving production excellence. The series has, to date, focused mainly on how best to construct such a subsystem and what activities it should pursue. In this concluding post, however, I want to return to the point of a CoPE, discuss signs of success, and evaluate the impacts it’s having.

This will require returning to our initial model for change, and will delve more deeply into points only briefly raised in the initial post. That elaboration should, I hope, provide sufficient guidance that organizations feel confident creating a CoPE of their own and working with their Honeycomb partner to provide an amazing experience to their users.

Signs of success

To begin, we’ll return to the model developed by Hébert-Dufresne et al. In this wonderful work, the authors note that neither a bottom-up first nor top-down first approach is sufficient to address the greatest challenges, which require coordinated group change. Each end of the spectrum must act mutually and reciprocally, and allow themselves to change for—and with—the other. As they make their incremental changes, there will come a point where a dramatic qualitative change occurs in the holistic system.

That qualitative change is increased cooperation through pro-social or pro-group behaviors. The actors involved are understood to require top-down institutional support to achieve this because those pro-group behaviors provide only indirect benefits. To sustain, compound them, and produce habitual cooperation requires not just their own activity, but also a conducive environment. As such, a CoPE should aim to grow pro-social behaviors amongst the organization’s members regarding practices that assist and inform their colleagues in their work to diagnose, improve, and maintain system performance. Exemplary activities include:

- Adding instrumentation according to established conventions.

- Revising those conventions once they’ve gone stale.

- Building dashboards to help on-call engineers quickly jump into action or onboard newcomers.

- Ensuring deploy markers are accurately denoting deploys and teams are checking the effects of their code changes once released.

These alone are not enough. In order to build towards that qualitative shift, the organization will need to adopt specific policies so that people repeat these things and establish a trend. Accolades and rewards may need to be rethought. For example, the NBA tracks and rewards players when they assist a teammate in scoring. Only when both happen in an amplifying cycle can a CoPE turn their colleagues’ behaviors into habits and make the desired change.

Measurements, or emotional support numbers

By now, it’s well-established that measures are corrupted once they’re put to work. That said, people still seek them out and they do perform a significant psychological function: promoting a feeling of agency and control in low-trust environments.

Organizations may insist on tracking something, so it’s good to understand the transformation that a CoPE is making so that we can create measurements around its impact.

Let’s note right away: the number and duration of incidents, unqualified by any other attributes, is a bad way to go. Much research as shown that categories like “incident” are constructed and change as sociotechnical factors shift. This makes univocally determining what an incident is and when it started/stopped is nearly impossible, so we should reconsider the idea that the best way to track this change is with an extensive measure.

What a CoPE is really after is making things better (a qualitative change). Is there a number or some other method of indicating that? Indeed there is!

Think of this change as an intensive one. Intensive properties, like density or temperature, are ratios of extensive properties. That makes them dependent on the context in which they’re situated. As the extensive quantities change, they induce changes in the intensive property, and vice versa; this change is analogous to the categorical changes mentioned above.

Given the number of factors at play in an organization, producing a single number is a significant challenge. We might look to something like modeling a weather system for inspiration:

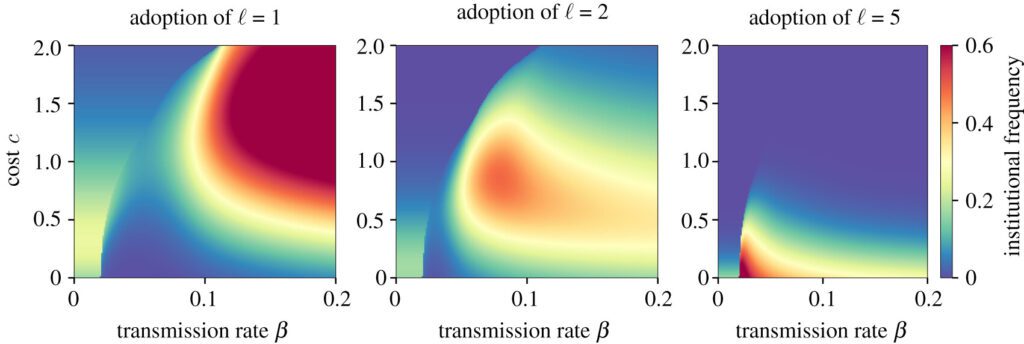

This dynamic model tracks several vectors and shows their relationship via a heatmap. It provides a high-level view of a system’s qualitative changes, which can then be analyzed to produce visualizations of more particular relations. Hébert-Dufresne et al. take this tack and use a suitable graphic to demonstrate results of their model:

As they say, this heatmap “highlights the phenomenon of institutional localization in which a given institutional level dominates the fitness landscape in some subset of parameter space.”

The switch to thinking in terms of intensive transformations may be outside the norm, especially if management is used to receiving One Big Number™. However, the adoption of techniques like this facilitates clear communication regarding the actually-desired information. That’s in contrast to using lossy signals like number of incidents and MTTR. Those are poor proxies and it doesn’t do anyone any good to report on them simply because they’re familiar.

Nonlinear progress

I’ll conclude with a final word on what it takes for a CoPE to succeed. Here I address myself directly to organizational management, and I urge you to heed these words.

Your position as an overseer in the formal hierarchy grants you certain powers. You often have the power to hire and fire, and own a budget. Don’t mistake that as sufficient. David Woods has called organizations “tangled layered networks.” This means that your formal position and power is only one layer among many others that compose your organization; you are yourself multi-functional and operate across layers simultaneously. Each layer has its own topology, and therefore, its own lines of force.

If you have decided that a CoPE is right for you, then for it to succeed, you may need to make certain tradeoffs against your position in the formal hierarchy in favor of another layer in the network. Don’t be afraid to do this. A true sign of leadership is knowing when to defer and to follow others. Be open to seeing the changes wrought by the CoPE as solutions to problems rather than as a problem to be solved, and to changing your own ways of working and being in your organization. This is part of why Charity has advocated the Engineer/Manager Pendulum, and why I mentioned sortition earlier. Swapping positions in one network may serve to address problems and allow for nonlinear progress.

Conclusion

This ends my series on the Center of Production Excellence. My goal has been to illustrate what a CoPE is and how it can intervene effectively in an organization. That institution is meant to solve problems. That means that it is a productive tangent, branching off from the limit that had been reached heretofore.

A tangent isn’t a linear continuation. If the organization could continue on linearly, then it wouldn’t be facing a problem. But it is, so something different is required. I hope that this, and Honeycomb, can be the solution to your problems.

For a list of the prior posts in the CoPE series, see below:

Pt. 1: Establishing and Enabling a Center of Production Excellence

Pt. 2: Independent, Involved, Informed, and Informative: The Characteristics of a CoPE

Pt. 3: Staffing Up Your CoPE

Pt. 4-1: The CoPE and Other Teams, Part 1: Introduction & Auto-Instrumentation

Pt. 4-2: The CoPE and Other Teams, Part 2: Custom Instrumentation and Telemetry Pipelines