It’s time we had a real conversation about why UX designers everywhere are still unhappy, why that elusive “seat at the table” feels so impossibly out of reach to so many (even at companies that embrace design), and how this impacts your business.

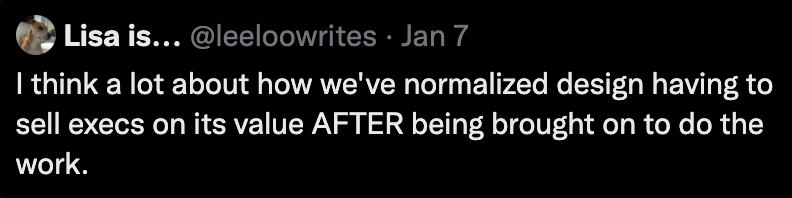

Design is facing down an epidemic of designers who feel burned out, taken for granted, marginalized, and disrespected. Yes, there is something different about our experience compared to other disciplines. Yes, your designer feels this way too. Some examples:

But how can this be? Aren’t designers highly compensated, sought-after professionals? Doesn’t every modern company talk incessantly about how important design is to their success?

Over the last 15 years, design thinking has gained momentum and prestige in the business world. Business leaders everywhere have come to see UX design as a differentiator and value generator; one they are willing to pay for and invest in. But while businesses have embraced the idea of design, many have also struggled to understand designers and the design process.

Imagine a bizarro parallel world where these companies realized one day just how critical reliability was to their bottom line. So they hired a team of highly paid site reliability engineers (SREs), then proceeded to get visibly frustrated every time an SRE tried to hold a retro or build a culture of writing better tests, doing code reviews, and paying down technical debt. Or they refuse to loop in an SRE when preparing to ship a new service.

“You’re slowing us down with all this testing!”

“I need response times to be faster, but instrumentation takes too long!”

Etc. etc. But you don’t get the results without the process, and you can’t jump to the end of the process. The design process can be messy and appear chaotic to outsiders. It isn’t linear—it changes depending on the problem being solved, the people involved, the results of discovery, technical challenges that emerge, etc. But there is always a process, and the process is the point.

Problem #1: Ship it!

Business loves organizational processes and predictable outcomes. Even the notion of “design thinking” revolves around the idea that you can replicate creative outcomes through a standardized process. Um, sure. But no. The creative process is inherently ambiguous, messy, unpredictable, and doesn’t belong to designers alone. Creativity involves chaos.

Design thinking isn’t something you pick up from a one-day workshop and it isn’t a step-by-step process that can be replicated over and over. Design definitely isn’t just making the product look good—it’s also a set of methods and tools designers use to foster creative thinking.

Design takes years to learn and practice, and it requires participation from everyone involved in solving the problem. Design thinking isn’t an output in itself, it’s a collaborative process that involves buy-in and trust from the whole organization to work. Designers rely on strong relationships with product, engineering, support, and sales to enlist and enable them to be part of this creative process.

Problem #2: A seat in the room?

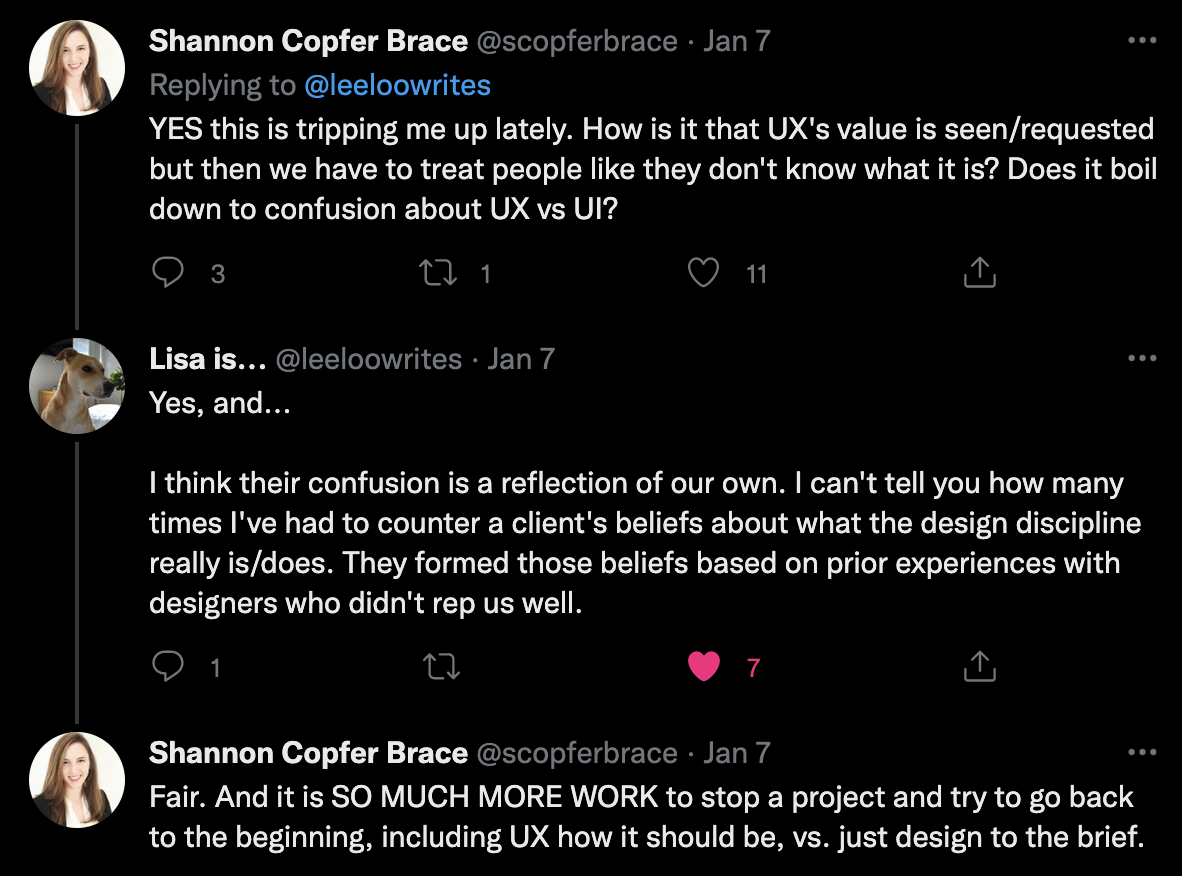

Shifting from a transactional relationship to a generative one is hard for everyone. Many companies have never had a designer on board before. If they have, it is typically in the marketing department where creative briefs are the norm. This model doesn’t work for product design (or marketing design—but that’s a whole other blog post), yet I see it being done over and over again.

For any function in a company to have an impact, they need to be part of the conversation. Designers need to be in the Zoom room or Slack channel where conversations about the problem are happening, and we need to be on an equal footing with product and engineering. Even more important, we need direct access to the customers affected.

Too many companies wait until they think they know the solution to a problem then engage design (again, acting like the job of design is making the solution look pretty instead of deeply engaging with the problem itself). Now the designer is in the uncomfortable position of slowing things down to learn about the problem, push back on assumptions, and ask questions that may have already been asked. This leaves designers feeling under-valued and left out of a process they were told they were going to be a part of.

Problem #3: Is it done yet?

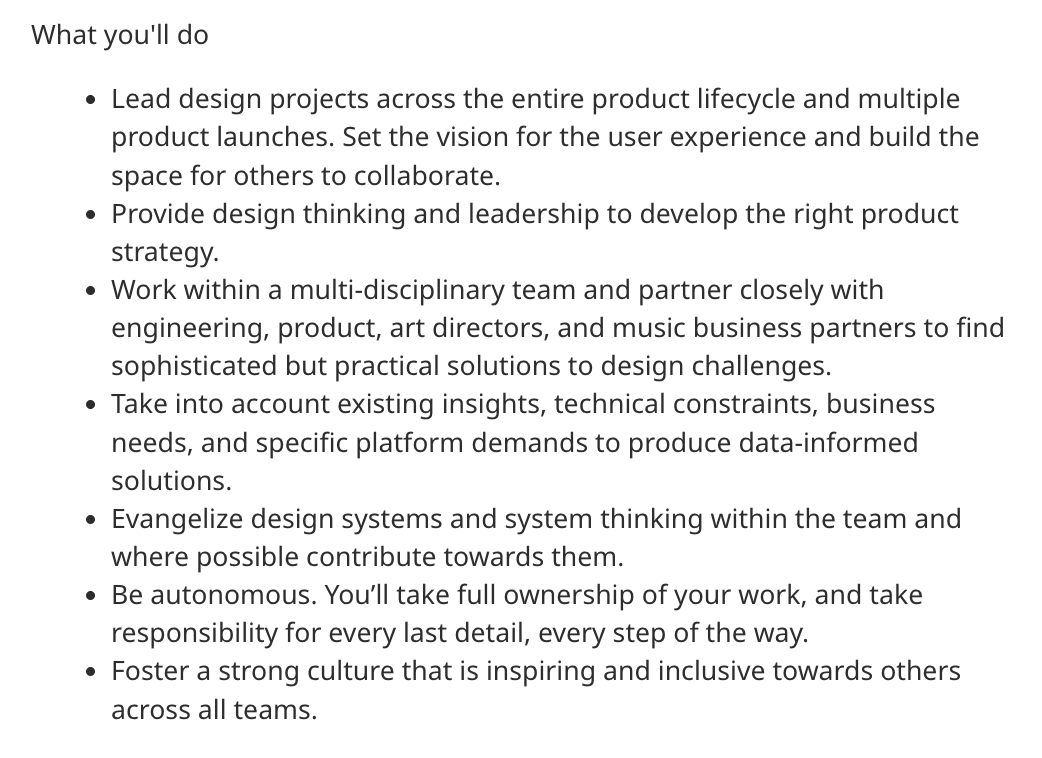

Unhappiness starts to creep in when you realize that all the enthusiasm and urgency around design is manifesting itself through unrealistic expectations. Many companies bring on one designer and expect them to:

- Educate about and establish a design culture where there’s never been one.

- Build the foundation of tools design needs to work quickly and effectively.

- Take care of a backlog of UX debt while shipping new features and delivering jaw-dropping visual design improvements.

Just one of the bullet items above could take an entire year with 1–3 designers working full time. If you don’t believe that businesses are really asking this of their designers, don’t take my word for it. Just go take a look at design job listings. Here’s one as an example:

Problem #4: Where are all the design leaders?

I’ve interviewed hundreds of designers over the years, and I’m still shocked by how many have never reported to a design manager. Not once in their entire careers. Even when there is design leadership in place, that leadership often reports into another function like Product or Engineering. In this survey by the Nielsen Norman Group, only 23% of respondents said their design teams reported directly to the C-suite.

Compared to other functions, design has an expanded, cross-functional role. It does not easily conform to how different departments are structured and operate. It requires the freedom and expertise to establish its method of practice, diplomacy, focused leadership, and most importantly, executive access.

Ideally, the design org should be a peer to engineering, product, and marketing, not subsumed under one of them. When it is subsumed, so is the voice of design. It causes design to lack visibility and input at the strategic level (this is part of why design is so often playing catchup to a project), and designers have to roll up to other functions that don’t understand how to advocate for design or resource design work. It’s a vicious circle.

If you see it, you can be it, right? It’s hard for many designers to see a path toward leadership when there are so few mentors and role models out there. The design leadership they do see is often fraught with tradeoffs, compromise, and burnout.

Problem #5: Stereotypes and assumptions

We’ve all heard about the diva designer, the hipster designer, or the emo designer. There is an overall view of designers as artistic dreamers that need to be given very specific directions otherwise they’re likely to go off into la la land. I’m not saying that designers like that don’t exist, but making assumptions about any group of people is harmful and wrong. More often, your designer is simply the most convenient scapegoat for broken processes and unsatisfying outcomes.

Who wants to work somewhere where you feel like people don’t understand what you do or don’t care about what you do or inherently don’t see the value in what you do? That’s the place a lot of designers find themselves in today.

What designers can do to make things better

Designers, you’re not stuck—you have the power to change the script. But it will mean learning new skills and using different communication methods than you are used to. It will be uncomfortable and feel awkward.

As a discipline, we need to face the reality that we have to be better at explaining the impact of our work to our peers, senior individual contributors, and leadership. We have to connect design work to the impact it has on the business in dollars and cents. This is not about proving the value of design; I would argue that has never really been in question here. Rather, we need to be able to better map the ways in which improving user experience supports the goals of the business.

Approach your team’s place in your organization as if it were a design problem—i.e., a misunderstanding of what it takes to achieve good design and how design impacts the bottom line. For example:

- Get better at telling the story of why your team matters to the organization, and how you support and move forward the goals and dreams it has for customers within the industry.

- Then communicate what you need to get there.

- Lobby for the staffing and resources you and your team need to achieve its goals, and always sell the impact and contributions design makes to the business.

If your company offers professional development resources, use them! Look for design coaches with experience making these connections for teams or attend workshops with this specific skill as a focus.

This is not about design changing itself to better suit the business world; rather, it is about designers learning how to talk about what we do in a way that business can better understand and appreciate what we bring to the table.

What business leaders can do to help designers

Designers are not special snowflakes, but their function is more process-driven and collaboration-driven than other functions. Take the time to talk to the designers and design leaders on your team and listen with an open mind. What are you expecting from design and are they set up with the support they need to deliver? Are the expectations realistic given the size of the team and the scope of the work ahead? If you aren’t sure, that’s ok! It is the perfect starting point for a conversation about what design needs to succeed and how the business can support them.

Designers can’t change the script on their own. They need managers within the business who are open to understanding what design brings to the table without trying to make it run like other functions. They also need mentors who can help them bridge the gap between design effort and business impact. This is new territory for many of them. For decades, design has mostly been treated as transactional and has not been close to where crucial business decisions and conversations are happening and being made.

Peers to design, what you can do to help

Understanding when and how to give design feedback can be very confusing. Seeing something for the first time is exciting and can raise so many ideas and questions that it can be hard to hold back your enthusiasm. But it is important to remember that design is a specialized function just like yours. It is about solving problems, not simply an aesthetic.

Designers undergo years of education and training to do what they do. Just like you, they have processes and procedures for handling all the work they are involved in. Remember this before engaging and ask yourself, “Is this feedback helpful? Am I engaging with the work that has already been done by the team or am I asking them to start over from scratch?” I speak for most designers when I say we would rather get all the feedback than none, but you can be a better partner to design by asking what kind of feedback they are looking for and what format they would prefer it be delivered in.

Be a champion for your designers! You can help raise awareness of the impact of design by mentioning them when showcasing your work. Did a designer help you in the discovery, research, or design phase? Talk about it! We do this at our demo days here at Honeycomb. When product managers and engineers show a new feature they’ve worked on, they invite the designer to say a few words about what went into the design portion of the work. It is a small gesture that goes a long way.

Design is crucial to business success

Yes, design can make or break a business. But design is not a quick fix or a short-term investment. It’s an investment in the long-term relationship of your product and its users. Great design makes this look effortless and easy, even obvious—but behind every pleasing interaction lies a messy, creative process with no guaranteed outcome at the start. If you aren’t prepared to invest over the long run in building a creative, generative design culture, that’s fine. Just be honest with your designers about how much support they can really expect. The mismatch between expectations and reality is what’s killing us.

Interested in learning more about UX design from the perspective of designers? I’ll be speaking at ConveyUX on May 4! Register here to attend.